Hergé and Zhang, Tintin and Chang: The tale of how culture unites in fiction and in real life

This year, fictional comic character Tintin, pop culture icon of the 20th century, turned 90. In this article, we take a brief look at the relationship his creator, Hergé, had with China and how culture unites.

On May 22, 1907, a boy who would grow up to influence his century through his comics was born in a quiet neighbourhood in Brussels, Belgium. The boy, Georges Remi, would later be known by his pen name Hergé—a clever way of spelling out the way his reversed initials are pronounced in French, his mother tongue. Hergé’s most famous creation, the series of 24 comic books entitled “The Adventures of Tintin,” has been translated into 120 languages and sold over 250 million copies worldwide. Every year, between 3 and 4 million copies are sold around the globe, of which 1,5 million are sold in China. And China, besides reading Tintin, has also been featured in it. But beyond the story told in the books, it is the story behind a particular volume of these books that serves as a real-life example of how understanding a culture has a positive impact.

Hergé’s character Tintin is a boy reporter who travels around the world and always ends up involved in (or gets himself into) dangerous situations to then save the day (instead of actually turning in articles). Over the course of the past 90 years since the very first comic strip of Tintin was published, the tales of Tintin’s adventures opened a window to the outside world for its readers and have captivated generations of children for its entertaining storylines and characters, and adults for its “geopolitical intricacy and psychological depth,” as the New Yorker once put it.

It has also amassed its fair amount of criticism and controversy, being deemed too biased at times, ungracefully stereotypical, and worse, racist, among other unflattering adjectives. Among the culprits, the earliest volumes stand out of the lot: “Tintin in the Land of the Soviets,” published in 1930, criticized for serving young Belgian readers of the time with anti-Soviet propaganda, and “Tintin in the Congo,” published in 1931, for portraying a paternalistic white colonial view of the then Belgian colony, Congo. These comics, as the author has said so himself in many occasions, were products of its time and went along with the European mentality of the early 20th century. But the fifth volume “The Blue Lotus,” published in 1936 and set in China, was a turning point in the series and in Hergé’s life; it was the author’s first volume based on extensive research, the first attempt to be faithful to the culture depicted. “The Blue Lotus” is revered as one of Hergé’s finest works and paved the way to the many others he would later create.

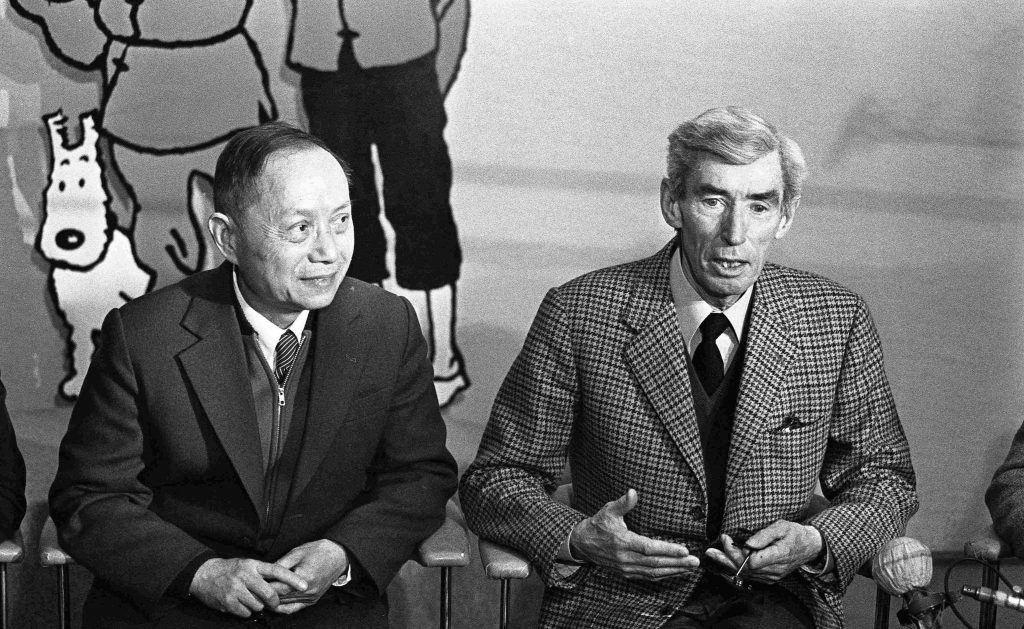

As a part of the background research on China for “The Blue Lotus”, one of young Hergé’s main sources of information and inspiration was a young Chinese student at the Brussels Academy of Fine Arts to whom he was introduced in 1934. Zhang Chongren had left Shanghai by boat the very same day Japan invaded China. His accounts of the events that unfolded prior to that day and of what happened afterwards through news relayed by his family that stayed behind in China deeply marked Zhang, and the bond him and Hergé formed in turn deeply influenced the story Hergé penned. Zhang and Hergé would meet every Sunday, and Zhang would help review “The Blue Lotus” to ensure accuracy. A few years later, Zhang Chongren returned to China, went on to lead the Fine Arts Academy in Shanghai and sculpted busts of some top political leaders, including Deng Xiaoping and French President François Mitterrand. And Hergé, needless to say, went on to become one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

It is thus no coincidence the boy Tintin befriends in “The Blue Lotus” is named Chang. This is the same friend Tintin travels in a desperate search to Tibet to rescue in the also highly acclaimed volume “Tintin in Tibet,” published in 1960. And like the fictional characters, Hergé and Zhang would only meet one last time decades after their first encounter, in 1981, when Zhang flew to Belgium. The reencounter aired on television in Belgium, when Hergé then declared:

“How can one describe the feeling one has when one meets after nearly half a century, someone who was more than a friend… someone who, as I said earlier, opened doors and windows for me on a whole civilization I knew almost nothing about. It was a world Zhang opened up to me.”

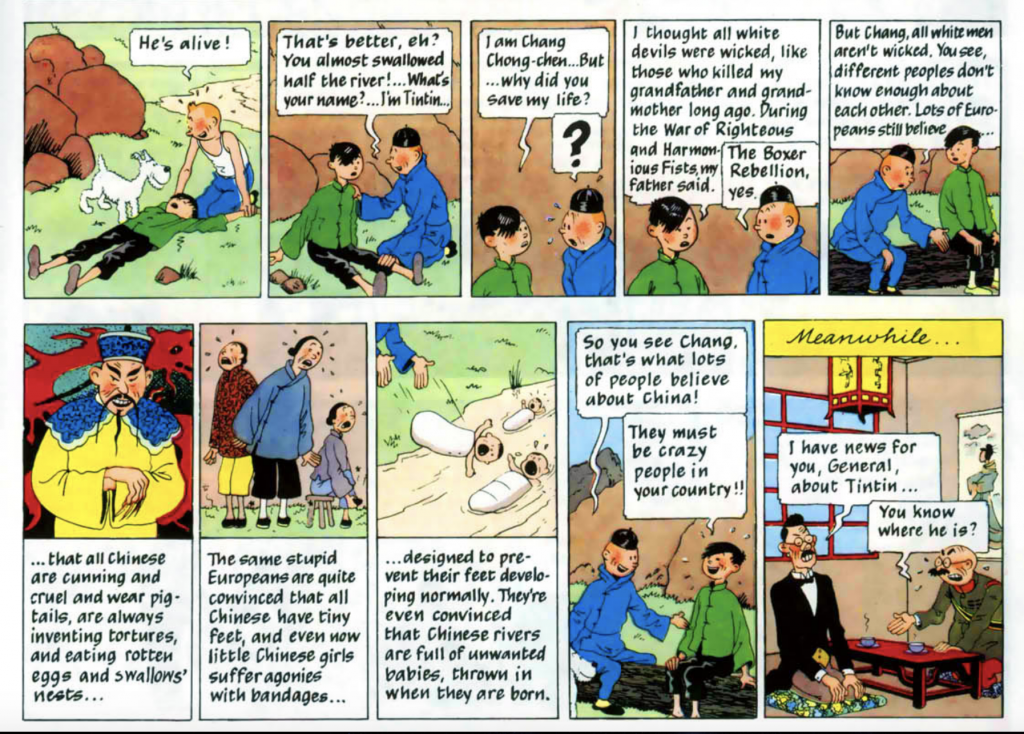

As much their friendship helped Hergé see China under a different light, it also influenced Zhang’s worldview. The encounter on paper between Tintin and Chang in “The Blue Lotus” is the best testimony to this, as Chang says to Tintin, “I thought all white devils were wicked, like those who killed my grandfather and grandmother long ago,” to which Tintin replies by telling Chang how most people back in Europe viewed China equally badly at the time, “…that all Chinese are cunning and cruel,” and so on.

Tintin starts his reply to Chang with a sentence that deeply resonates with us, as he says, “You see, different peoples don’t know enough about each other…”

The Hergé Museum in Brussels, Belgium, is a museum dedicated to Hergé’s life and work, including “The Adventures of Tintin” and many other comics and artworks. Shake to Win is proud to have Musée Hergé as one of the many authentic and culturally rich spots on our app. It is a special and dear place for us, but not only. If you would like to know more about Hergé and his timeless contribution to world culture, this museum is the place to visit.

About Shake to Win

Shake to Win connects Chinese independent travellers with authentic places and cultural experiences around the world. Because our users care about culture and so do we, Shake to Win offers local businesses who represent the local way of life an easy, hassle-free way to reach Chinese independent travellers.

We want our users to have the best, most authentic experience during their travels. We also want local places and businesses we love to be able to attract Chinese visitors who respect the local culture. Our app contains listings of experiences, businesses and cultural institutions selected by our team with both our users’ preferences and customer needs in mind.

The Shake to Win app also provides businesses with the possibility of offering our Chinese users incentives with only a few clicks. This is a thoughtful, culturally sensitive way to let travellers know long before they arrive at your doorstep that they are welcome at your shop and will be well received.

Joining Shake to Win is really easy. No need to know Mandarin, set up Chinese social media accounts, or even leave your office. Get a free listing on our app and let a new China get to know you.